A second day cycling along the Ho Chi Minh Road brings fabulous scenery, banh mi madness and a chance encounter with a film crew.

The day started with what can only be described as a breakfast ‘bun fight’ when I inadvertently stumbled upon Huong Khe’s most popular banh mi stall in the early morning peak.

Yep, turns out that 6am is rush hour for Banh Mi Hue and in the grey light I witness the stall rapidly turn from quiet to a shemozzle as dozens of customers arrive at once. Fighting against a swirling tide I fight to get in an order of a fried egg roll.

Unfortunately I wanted a fried egg banh mi, and that involved someone going out back to cook the egg – and the ladies were getting smashed.

“I can’t remember!!!” the younger one wails as orders are are shouted haphazardly her way (there’s obviously no queuing: this is Vietnam after all).

At one point a customer – tired of waiting to pay – flings a handful of bank notes in the direction of a plastic bucket which forms the makeshift till.

It misses.

A handful of notes flutters for a moment in the air then plonks straight down into the sauce container. The older lady deals with it without missing a beat, plucking out the money and stashing it under the table.

Sandwich finally in hand, I make a hasty retreat.

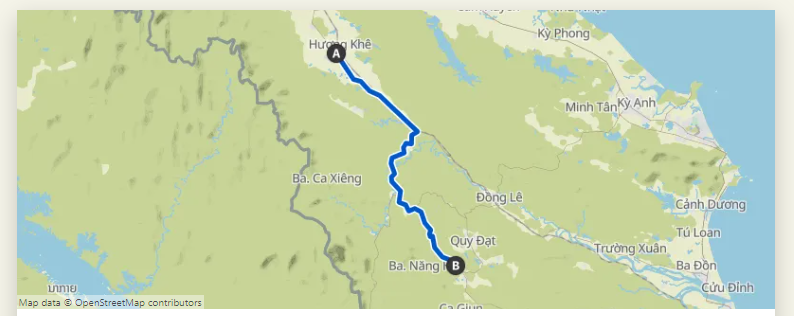

Cycling the Ho Chi Minh Road: part two

Hitting the road, I continued for another 75 kilometres along one of the most scenic sections of the Ho Chi Minh road, which forms a 2000-kilometre spine through the interior of Vietnam.

Rising in altitude, the jungle became more and more dense and I was treated to sweeping views as I cycled along a ridge line

It was easy and fun cycling along the road, stopping to enjoy the views before plunging gloriously into a valley.

This region was also more sparsely populated though occasionally I pass stacked lorries, or warehouse where thin yellow logs were being stacked and loaded.

Apparently the eucalyptus trees farmed here are now in hot demand in Europe where firewood is needed in place of Russian gas. A I stop for a coca cola along the timber yard next door is a hive of activity, and workers join me for photos before I head off.

I also couldn’t resist checking out this cute rural train crossing just past La Khe village, which was just crying out for a photo shoot with the local railway attendent. She let me know there were about 15 trains a day through the crossing.

Luckily she was well up for a photo.

I also pass several groves of rubber plantations. The neat, symmetrical rows, combined with whatever music is in my head phones) have an almost hypnotic effect.

The last homestays before Phong Nha

Even after 75 kilometres I could easily have kept on cycling, but two (highly recommended) homestays just out couple of homestays offer the last available accomodation before the Da Deo pass and its dramatic gateway through to Phong Nha.

Where most motorbike travelers would push on to the tourist mecca (relatively speaking) of Phong Nha, one of the lovely things about bicycle travel is being ‘forced’ to stop and discover these wonderful in between places.

Rolling in to the Nha Nghi Anh Linh, the proprietress Loan is beyond excited to let me know that another Australian guest would be arriving that afternoon, bringing with him a film crew.

Intrigued, and to be honest more than a little starved of conversation, I keep an ear out for their arrival.

While the “Australian” turned out to be Belgian and the arrival time more like 9pm, it was still good to chat with the film-makers partners, who had made a staggering 20 hour train journey up from Saigon.

Fascinating filmakers tell a story of borderland cultures

They’d rushed up to the village in the hope the hope of capturing a very specific local cave in flood. The cave was central to their short film project, which told the life story of a local Ruc woman.

Sixty years ago she’d been born and raised in the cave, in the tradition of the Ruc ethnic group, seen as one of the most mysterious of all Vietnam’s 54 minority groups.

Traditionally the Ruc dwelled in caves, living as foragers, with some cave areas only accessible by boat. These days people still return to the caves for part of the year to keep their culture alive.

Sadly, the next morning the news came through that there was no water at all in the cave, but it was easy to understand why they’d undertaken the journey.

Huge floods had just hit coastal areas of central Vietnam but the vagaries of Vietnamese weather patterns meant that Trung Hoa had stayed dry.

The quietly spoken Belgian and I lamented the futility of weather forecasts in this land of mountains and sea.

“I look at five different weather apps and they’re all different,” he said.

“Then the actual weather is still different again!”

His Vietnamese colleague, who’d discovered the story enthused about the beauty of the area: “Turn left just up here and everything is amazing!”

“But you won’t be allowed,” the Belgian explained “We have to get permission in advance for everywhere we go. It’s very sensitive.”